Treating CTO: A New Approach to Coronary Intervention

Over the last two decades, there has been an increasing interest in new techniques developed for the treatment of chronic total occlusion (CTO). In this article, cardiologists Dr Kenichi Sakakura and Dr Soon Chao Yang share their input on the ongoing challenges and opportunities available to patients seeking treatment.

WHAT IS CTO?

Chronic Total Occlusion (CTO) is commonly defined as a total obstruction of a coronary artery for at least three months. In simple terms, a CTO refers to total blockage of a coronary artery. In younger CTOs, there is a soft cholesterolladen material within that which becomes progressively harder with time, making it more difficult to treat.

The development of a CTO can result from acute myocardial infarction (AMI), commonly known as a heart attack, where one’s heart muscles sustain damage as a result of reduced blood flow. Patients with CTO have a higher risk of coronary disease and higher rates of diabetes and stroke, among others.

“Most CTO comes from acute AMI that goes untreated. Some patients that suffer from silent myocardial infarction may not feel symptoms, only a heaviness in the chest, but they may go on to develop CTO if they don’t seek treatment,” says Dr Kenichi Sakakura, an associate professor at the Department of Cardiology at Japan’s Jichi Medical University Saitama Medical Centre.

Other common symptoms include chest pain or discomfort which may travel into the shoulder, arm, back, neck or jaw. It is also possible for CTO to occur unnoticed and without symptoms, which demonstrates the importance of regular heart scans for people at risk.

“Risk factors of CTO are the same as a general coronary heart disease and it is a consequence of severe coronary heart disease,” says Dr Sakakura. “That means there are no specific risk factors, but diabetes, hypertension and smoking increase the risks.”

The toughness of the fibro-calcific material within a CTO represents a common and significant challenge to interventional cardiology and has direct implications on the kind of intervention strategies used in treatment.

INNOVATING THE PROCEDURE

Japanese cardiologists have been pioneers in the field of CTO intervention and have spearheaded the development of new Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) procedures to treat CTO. Their success rates have been difficult to replicate elsewhere.

“This procedure was done mostly by Japanese doctors from 10 to 15 years ago and at that time the success rate of this procedure was not so high, around 60 to 70 percent success rate and the long-term outcome of this procedure was not great. Around half of the patients suffered from restenosis (repeated episodes of narrowing blood vessels),” explains Dr Sakakura.

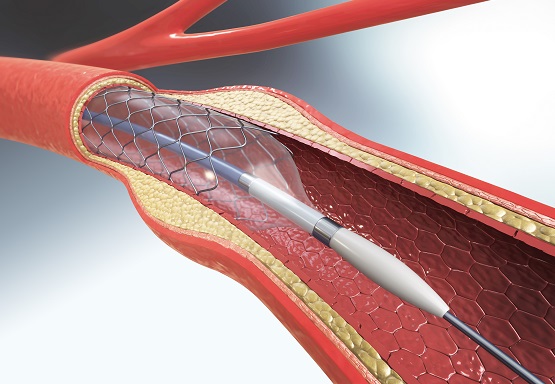

PCI uses a thin flexible tube called a catheter to place a small structure called a stent inside a patient’s artery, which is used to open up blood vessels in the heart that have been narrowed by plaque buildup. When Japanese specialists began performing this intervention, long-term outcomes were not ideal. But that has changed over time, and the contrary can be seen today.

“Japanese doctors have developed new procedures for CTO, especially the retrograde approach. This new technique uses the collateral branch to penetrate CTO bidirectionally, which pushed the success rate to 80 percent, so this is big progress in this procedure,” says Dr Sakakura, adding, “Now, doctors all over the world are interested in CTO PCI procedure because success rate is high and long-term outcome is good.”

The retrograde approach developed by Japanese cardiologists simultaneously dual-penetrates a patient’s arteries using guidewires as a means to determining characteristics of the CTO including lesion length and other factors.

“Retrograde is not so common in Singapore; we’re a few years behind Japan in that respect. When I trained in the US about nine years ago, there was no such thing as retrograde approach. It was not thought to be possible to go from one artery to the other,” says Dr Soon Chao Yang, an Interventional Cardiologist.

“CTO means that the whole artery is blocked off. Think of it like walking into a misty day and you can’t see the road in front of you. You’re driving blindly into where you guess the blood vessels are. When we take an angiogram, it’s 2D rather than 3D so you need to visualise the path taken when performing the procedure. It’s never simple and no two people have the same blood vessels,” says Dr Soon.

Prior to the development of the retrograde approach, a traditional antegrade approach was used with limited success due to the difficulty of effectively traversing the CTO. Failure commonly occurred due to the antegrade wire failing to make forward progress.

“We enter by placing two tubes in the femoral artery, which are two large blood vessels near the groin, with one tube on each side which we send the guidewire into. Think of it like a train track,” says Dr Soon.

“Retrograde is more successful because you go through the rear blood vessels from the backside and while showing the other wire where to point to, so you know which way to go – with the antegrade approach, it’s like going in blind.”

“It’s the Japanese who created this new PCI method.” says Dr Soon, adding, “Because of this innovation from Japan, other countries are trying to catch up. More and more interventionists are trying to attempt it.”

THE SINGAPOREAN CONTEXT

CTO cases in Singapore have been increasing year by year with patients more willing to opt for PCI intervention, but there is still discussion about whether and when CTO should be treated due to the procedure’s higher complication rate and difficulty of execution. Many interventional cardiologists are reluctant to attempt PCI without having direct experience of knowing what to do.

The hospital recently treated an unusually complex CTO patient using both antegrade and retrograde approaches in two different procedures with partial success. The patient, a 61-year-old male, opted for PCI over concerns that he would be a high-risk candidate for bypass surgery due to the fragile state of his lungs after decades of smoking.

“In Singapore, we’re a bit different from Japan as we offer CTO patients bypass surgery as a first choice. This patient has bad lungs from long-time smoking, leading to high bypass risk. So that’s why we’re trying the PCI approach with him. The vast majority of CTO cases in Singapore are treated with bypass surgery,’ says Dr Soon.

“This is a typical patient who suffers from an ostial left anterior descending lesion, which means his central artery is already blocked off totally right from the start. This makes it one of the hardest procedures to do, especially by antegrade approach,” he adds.

The retrograde approach remains a non-standard practice in Singapore. Patients in Singapore are offered bypass surgery as a first choice, but if retrograde PCI became more prevalent, many could opt for it due to its less-invasive procedure, which typically lasts three to four hours and requires one to two days of hospital treatment.

“Retrograde approach is not easy. If you operate on a CTO using only antegrade approach, the process takes one to two hours. However, with retrograde approach, it takes three to four hours to finish, says Dr Sakakura, adding, “nevertheless, this procedure uses only local anaesthesia, so the patient is conscious and can walk the next day, so that’s why this procedure is attractive for doctors and patients.”

Generally, the rise of PCI treatment for CTO has improved the symptoms and prognosis of patients suffering from the chronic and stable phases of coronary disease. Current data suggests that successful PCI is associated with improvement in patient symptoms, quality of life, ventricular function and patient survival.

Currently, CTO PCI success rates of greater than 80 percent are being reported in specialist Japanese, American and European centres. Despite this, referral for CTO PCI remains low in many countries and the historically poor success rates that characterised early interventional experience continue to affect referral behaviour. PCI success rates have also remained relatively low outside of specialised centres.

“Most interventional cardiologists believe PCI can improve patient outcomes but if we are unable to penetrate and treat CTO, then the PCI doesn’t work, it is recommended that the patient opts for bypass surgery,” says Dr Sakakura.

Patients at risk for CTO are advised to seek diagnosis with the aid of coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA), which generates a three-dimensional image during a CT scan that examines the arteries supplying blood to the heart to determine whether they have been narrowed by plaque buildup.

“These days, CCTA is very popular and good for diagnosing CTO, that’s why in Japan we frequently use it at outpatient clinics,” says Dr Sakakura.

The hospital offers CCTA using Siemens Flash technology that is able to accurately diagnose CTO. Perhaps the key to PCI’s popularity in Japan lays in the popularity and accessibility of CCTA machines, which offer a clear view of the coronary artery while being less invasive than a traditional coronary angiogram procedure.

Article contributed by Dr Soon Chao Yang, an accredited doctor of Mount Alvernia Hospital.

This article is taken from our My Alvernia Magazine Issue #29. Click here to read the issue on our website or on Magzter.